Rosetta spacecraft back on track (and ready to rendezvous with comet 67P)

In the not too distant future, scientists across the globe may be privy to an array of photographs, research material and never-before-seen footage of comet 67P, a roughly 3km-by-5km-large rock discovered in 1969 by Klim Ivanovych Churyumov and Svitlana Gerasimenko.

The European Space Agency’s comet-chasing spacecraft, named Rosetta, has been tracking 67P for nearly a decade, and is officially back on track after three years of hurtling through space in silent hibernation.

Launched in 2004, the Rosetta probe’s never-before-attempted mission is to chase down a comet – specifically 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko – and place a robot on its surface.

Once the car-sized craft and robot lander, called Philae, secure a landing on the comet, they will gather evidence daily from 67P for a period of over a year, with the aim of contributing towards humankind’s understanding of the evolution of the solar system and the role comets may have played in the Earth’s development.

As of 20 January 2014, after 957 days of hibernation when the craft’s solar cells didn’t have access to enough sunlight, the Rosetta spacecraft was back on track, all systems “go”. The craft transmitted a message back to Earth, indicating its proximity to Jupiter and its successful recharge of the solar cells that power it.

Journey to the end of the solar system

Rosetta first circled Earth and Mars in the inner solar system before moving outwards to Jupiter, which now brings it on course to track Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

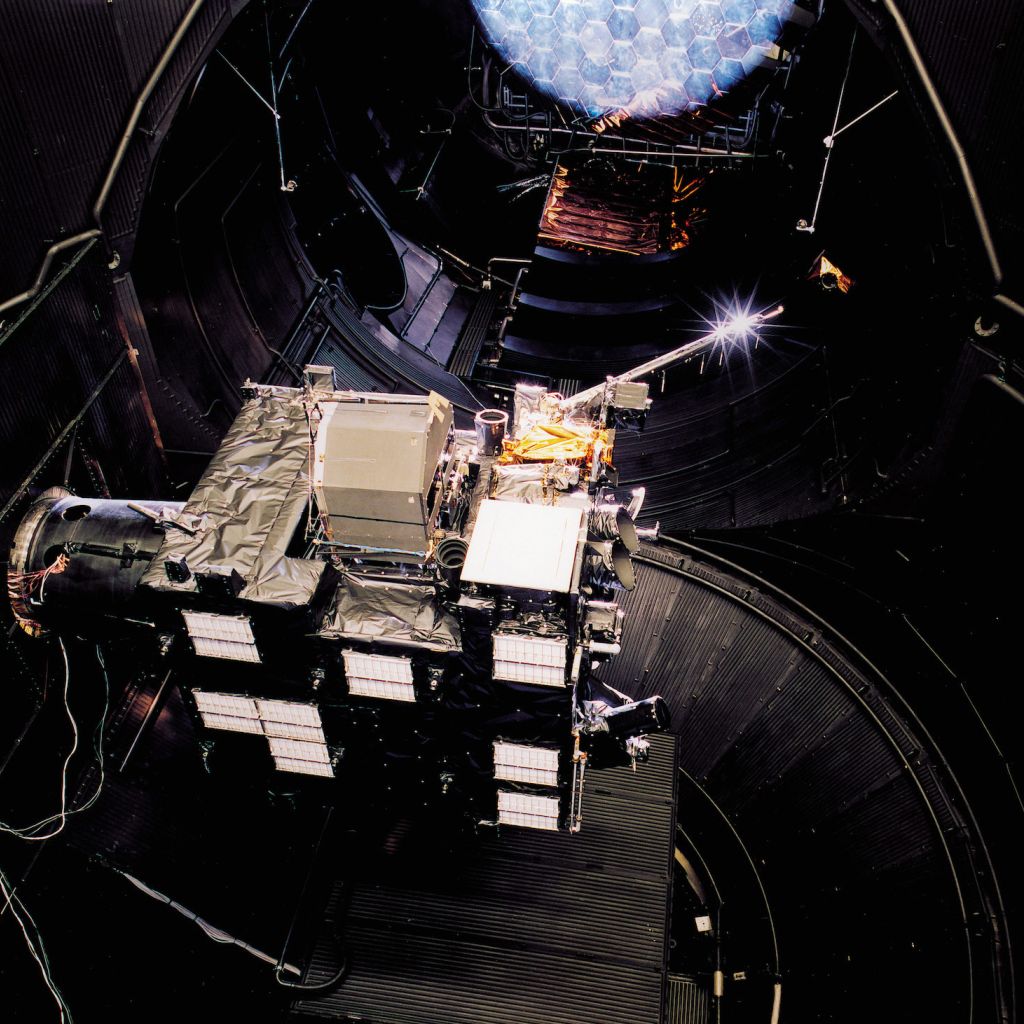

At this stage, with all solar cells firing, mission controllers can beam the probe a series of commands to ensure that subsystems and 21 scientific instruments aboard the spacecraft and Philae are in working order.

Once the controllers are satisfied, and the craft is close enough to the comet, the probe will begin to scan the surface for a suitable place to drop its lander. This is expected to take place in November this year.

If successful, the mission will represent an array of firsts: it will be the first time a probe has landed on a comet’s nucleus; it will be the first space mission to venture beyond the main asteroid belt – more than 800-million kilometres from the sun – using just solar cells for power; and it will be the first time a lander has the opportunity to capture images of the surface of a comet.