Astronomers announce discovery of closest-ever exoplanet

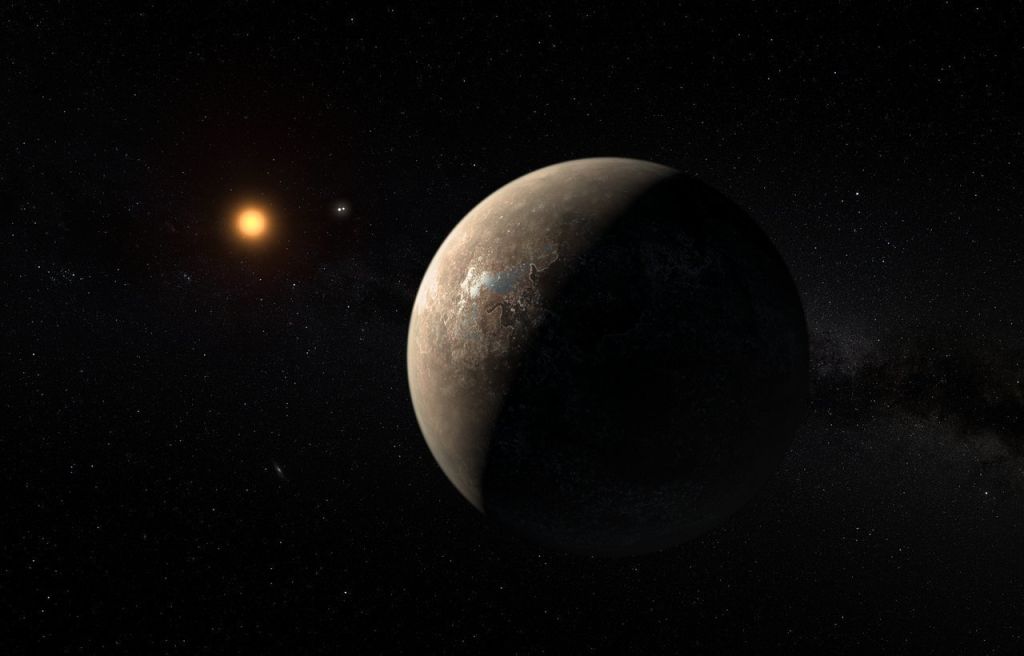

In what may turn out to be the biggest scientific find of recent time, astronomers have announced the discovery of an Earth-like planet in orbit around our next-nearest star, Proxima Centauri.

While exoplants – any planet outside our own solar system – have been found around hundreds of stars in our galaxy since 1988, this is the closest. A paper published in Nature suggests that it could be a terrestrial planet, made from rocks and metals, like the Earth.

It would present the best chance for humanity to see what an exoplanet actually looks like, and one day, we may even be able to visit it.

After all, it's only a mere 40-trillion kilometres away from Earth.

The scale of the universe

The universe is a very, very big place. Our moon is 384 400km away, and it took Apollo astronauts about three days to reach it. With current technology, it would take about six months to reach Mars. NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft has been travelling through space for 39 years, and at its current speed of 17km per second, it has only just reached the edge of our solar system.

But that's nothing. Using conventional rockets, it would take at least 30 000 years to get from our star, the Sun, to the next one, Proxima Centauri. And so far, we're only talking about two stars in a galaxy of one hundred billion!

So how was this exoplanet even discovered? Turns out, the little tug of gravity from the planet causes Proxima Centauri to “wobble” slightly, and this shift in light can be detected by telescopes.

How's the weather?

We're going to need much, much bigger telescopes before we are able to get a good look at the planet, named Proxima b, but the researchers were able to figure out some details of what it might be like.

Since it is so close to its star, the planet has a very fast orbit – a year lasts just 11.2 days on Proxima b. The star is smaller, dimmer and cooler than our sun, but way more active, throwing flares and x-rays out into space, and likely battering Proxima b with radiation.

This has a few implications. Proxima b could fall within its star's “habitable zone”, at just the right distance away for liquid water to exist (not too hot so it evaporates, and not too cold so it freezes).

But planets that close to their stars tend to be “tidally locked”, meaning that half the planet is constantly in daylight and the other in darkness. This can also lead to one half being barren and scorched, and the other frozen and hostile.

Could life ever evolve from conditions like these?

Maybe. That will be the topic of debate among scientists for years to come. For now, the signifance of the announcement is still being fully understood.

“Just the discovery, the sense of exploration, of finding something so close, I think it is what makes [it] very exciting,” Guillem Anglada-Escudé, co-author of the research from Queen Mary, University of London told The Guardian.

Timeline to the stars

So, how soon until we get to see Proxima b? The most powerful space-based telescope we have only launches in 2018, and probably won't be big enough to catch a glimpse. The only Earth-based telescope that has a chance goes online in 2024.

We may, however, be able to visit Proxima b with tiny nanosatellites. This blog reported on Professor Stephen Hawking's Breakthrough Starshot project back in April, and reportedly, the research team behind Promxima b's discovery have been in touch with the Starshot team about changing their target.

That technology is probably a few decades away, but once ready, Starshot could accelerate these tiny nanosatellites to an incredible 215 million kilometres per hour. At that speed, they could make it to Proxima b in about 20 years.

We're not going to see the results of these endeavours in our lifetime. But that has never stopped the pioneering spirit of humanity.

As astrophysicist Carl Sagan once said:

“The size and age of the Cosmos are beyond ordinary human understanding. Lost somewhere between immensity and eternity is our tiny planetary home. In a cosmic perspective, most human concerns seem insignificant, even petty. And yet our species is young and curious and brave and shows much promise. In the last few millennia we have made the most astonishing and unexpected discoveries about the Cosmos and our place within it, explorations that are exhilarating to consider. They remind us that humans have evolved to wonder, that understanding is a joy, that knowledge is prerequisite to survival. I believe our future depends on how well we know this Cosmos in which we float like a mote of dust in the morning sky.”