Why hominids are responsible for the meat and veg on your dinner plate

With the festive season upon us, it’s time to take a break from work and turn our thoughts to family gathering and the inevitable reason for many of those gatherings: food.

Food has, unsurprisingly, played a pivotal role in shaping who we are today. Think about the very first human, who, diving among the tidal pools of a rocky shore, spotted a strange, hard-shelled insect-like creature with pincers and feelers under the water and thought: “I wonder what that tastes like?”

We can thank countless unnamed ancestors who put their stomachs on the line in the pursuit of figuring out what would kill us, and what wouldn’t.

Generation after generation of such knowledge has resulted in modern human gastronomy, an extremely broad range of foods that encompass all manner of regional tastes. Most members of our species are omnivores, which means they eat meat and vegetables. This is only possible in modern times due to large-scale farming: we plant, grow, pick and distribute our veggies, and we have domesticated animals specifically to be eaten.

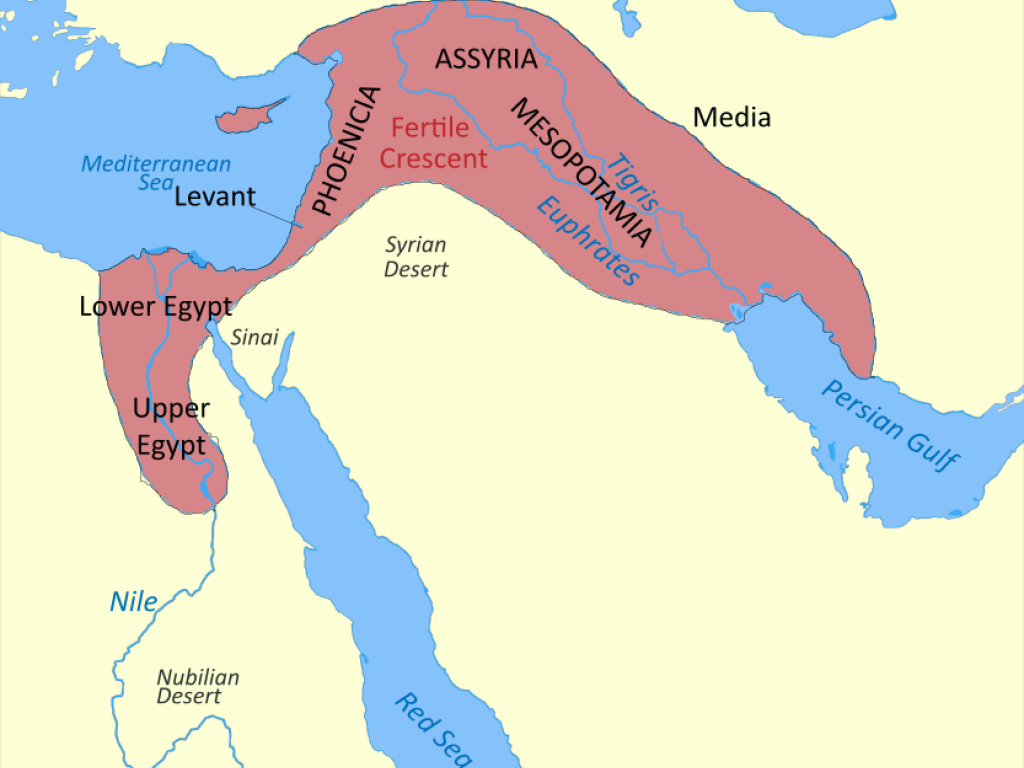

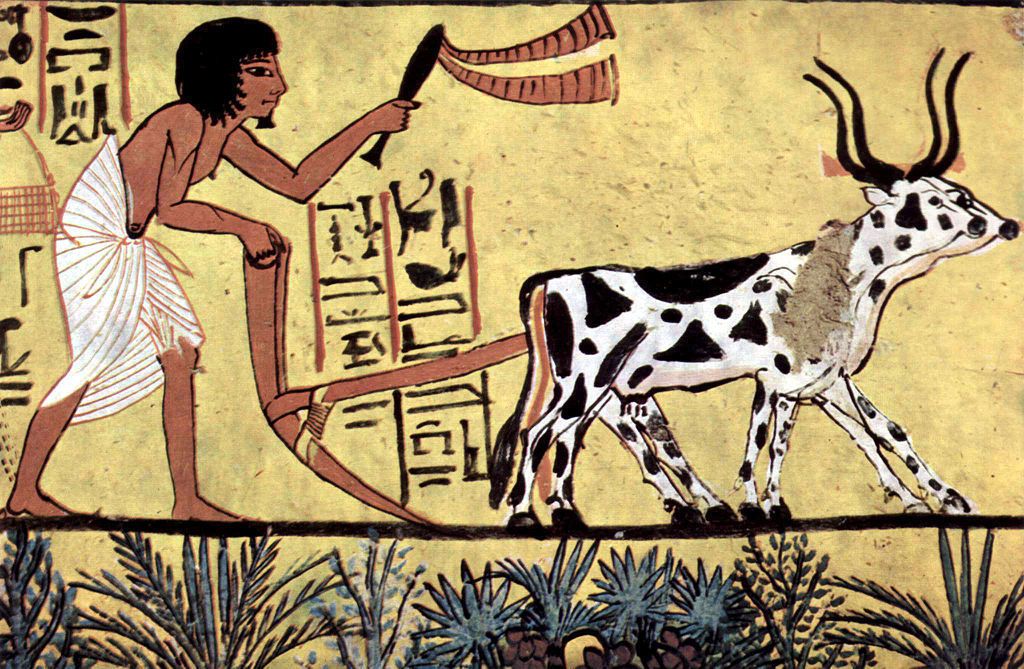

On the time-scale of Homo sapiens, agriculture is fairly new. Around 6 000 years ago the area that we call Iraq today used to be very fertile, sandwiched between the mighty Tigris and Euphrates rivers. People living in the area started planting and harvesting seeds, and learned how to plough and irrigate the land.

This changed everything. Up until that point, humans had to move around to ensure a food supply. Like other animals, the name of the game was survival. Now, they could shirk their nomadic ways and form permanent settlements. They weren’t just making enough food to survive, they were making surplus food that could be stored for later use.

The impact was enormous. It created the rise of civilisations, the necessity for writing, mathematics, and timekeeping. Agriculture made us who we are today.

But why meat and vegetables? For that, we need to go further back. According to Brendon Billings, Maropeng’s Bone Detective and University of the Witwatersrand scientist, about 2.5-million years ago there were two groups of hominins who would not have looked entirely human, but who walked upright.

While one group preferred vegetables, they did eat a bit of meat. Everything they ate was raw, so they had very different mouths to ours – big, powerful jaws for crushing seeds, hard nuts and other vegetation. Basically, this animal had a tough consistency in the diet,” says Billings.

The other group ate a balance of meat and vegetable matter, and it is believed that they were able to make fire, or as Billings suggests, perhaps they were foraging and would opportunistically find a carcass that had been caught in a veld fire or fire caused by lightning, so they could eat cooked food. They had much smaller jaws and teeth, more similar to ours.

“This animal had a less consistent dependence on harder foods,” Billings explains, adding that recent data on micro-wear of tooth structure indicates that both groups had a similar diet but the one (robustus) is more consistent with a harder, tougher diet than the other (gracile Australopithicines).

Of these two groups, the latter would eventually evolve into modern human beings. Our direct ancestors, thought to have derived from Homo ergaster, share the same genus as our own species, Homo sapiens. Fossil records indicate that their evolutionary line came to an end just over 1-million years ago.

Scientists say that eating meat was essential as the intake of protein and the synthesis of the muscles and brain led to the brain developing over the next 2-million years. Protein ingestion never resulted in brain development per se, but provided the means to accommodate a developing brain. Interestingly, Billings says insects provided a good supply of protein to accommodate the needs of a developing brain.

The earliest fossil evidence of controlled fire in southern Africa was discovered at Swartkrans and dates back about 1-million years. Think about that the next time you are gathered around the braai this festive season.