New bipedalism study keeps scientists on their toes

The ability to walk erect on two feet – bipedalism – is a feature unique to humans and one of the fundamental differences between ourselves and closest living relatives, apes.

In a study featured in an article on the University of the Witwatersrand’s (Wits) website under the heading “Big toe’s big bone holds evolutionary key”, a team of scientists shares the importance of the study, a fresh approach to the subject, and why establishing exactly when humans walked upright remains one of the burning questions facing palaeoanthropologists.

Bipedalism studies have moved a step closer to resolution following the new analysis method developed by the interdisciplinary team at Wits.

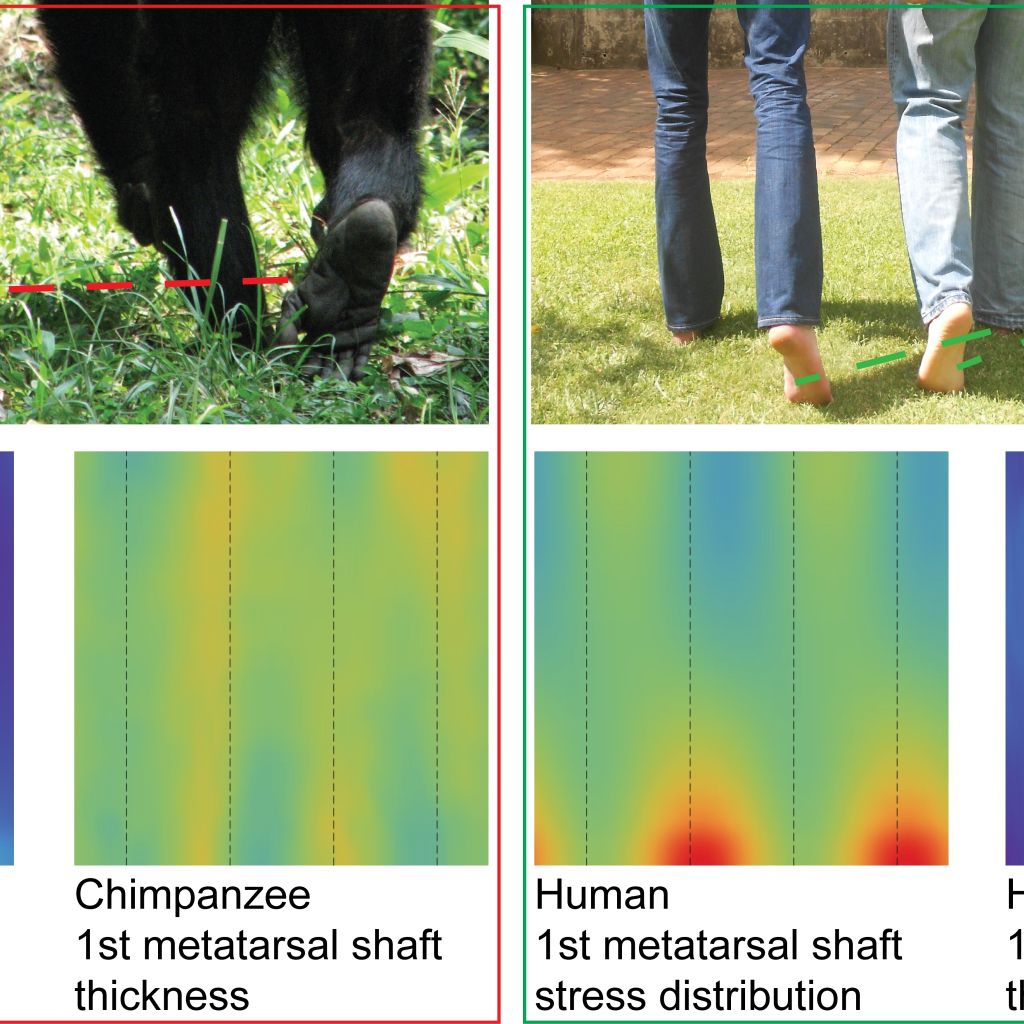

In the study – “Cortical structure of hallucal metatarsals and locomotor adaptations in hominoids” – published in the open-access online journal Public Library of Science, scientists highlight foot differences between living humans and other apes. The elements that set the two species apart will form the basis for further studies to establish when the modern human bone structure in the hallucal metatarsal first emerged.

The study was conducted by Dr Tea Jashashvili and Dr Kristian Carlson from the Wits Evolutionary Studies Institute; Mark Dowdeswell, a senior lecturer in the Wits School of Statistics and Actuarial Sciences; and Dr Renaud Lebrun, a research engineer at the French Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution de Montpellier.

As well as providing critical insight into the first appearance of the modern upright gait, the study will provide data to “significantly advance the study of bone biology and functional morphology in hominin fossils”.

“This approach shows tremendous research potential for bone biologists and functional morphologists, particularly those interested in limb structure,” says Jashashvili.

In terms of specifics, the team focused on the shaft of the foot bone that is connected to the big toe, otherwise known as the hallucal metatarsal, comparing the structure among groups of modern humans, gorillas and chimpanzees.

The big toe, or hallux, is integral to the propulsive part of walking upright and running in humans.

This is illustrated by Professor Suzanne Kemmer, Associate Professor of Linguistics and Director of Cognitive Sciences at Rice University in the US. In her response to an excerpt from Wikipedia, she comments, “Unlike humans, apes are critically dependent on their hands (particularly the knuckles) for walking. Freeing of the hands was a consequence of the adoption by pithecanthropoid and anthropoid primates of erect bipedal walking.”

In other living apes the big toe is more thumb-like, affording the prehensile ability that apes need for climbing and feeding.

The team’s study documented structural differences between humans, chimpanzees and gorillas, some of which were surprising. “We are eager now to begin examining how far back in evolutionary time these differences can be traced,” says Carlson.

Maropeng’s Path to Humanity exhibit explores adaptations such as this over millennia by exhibiting a wealth of fossil evidence that depicts hominin advancement.