Stare into the face of the oldest human ancestor

It’s time to meet your potential great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great [this goes on for several thousand lines] grand-relative.

Do you see any resemblance?

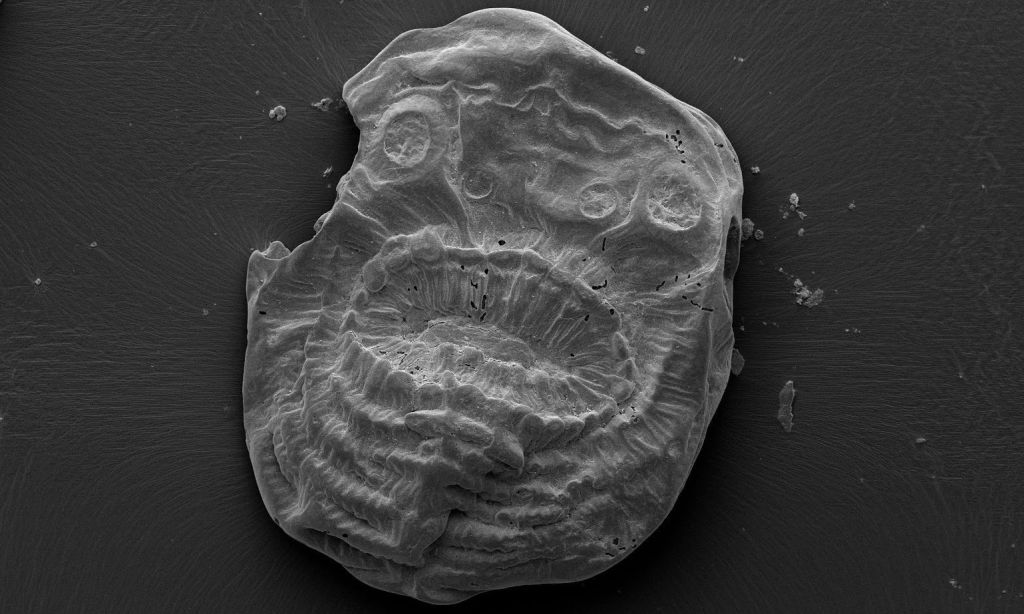

This is the face of Saccorhytus coronarius, reconstructed from tiny microfossils discovered in China.

A recent study has determined that this is the oldest example yet discovered of a kind of animal called a deuterostome, and guess what – you’re a deuterostome too!

Who’s who in the zoo?

Biologists have come up with many ways of dividing up and classifying living things into different groups. All human beings alive today belong to one species, homo sapiens. We are also primates, a particular kind of mammal, and beyond that we are also vertebrates (animals with backbones).

The broader the group, the more wildly different kinds of animals you’ll find in it.

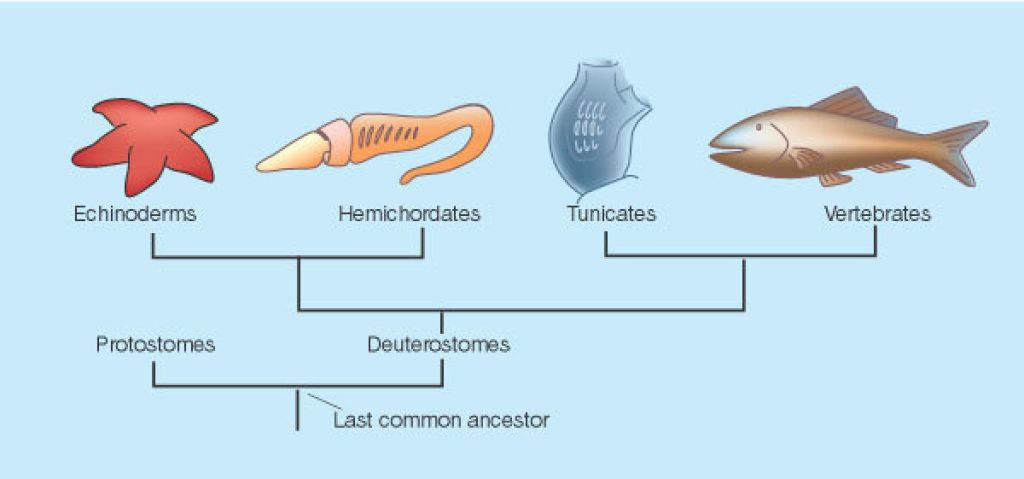

Deuterostomes are a pretty broad group. It includes any animal where the embryo develops two openings – a mouth and an anus – with the latter forming first.

This puts us in the company of starfish and acorn worms. It is also the opposite to how animals such as insects, molluscs and other worms develop; they are classified as protosomes.

Family reunion

It’s hard to get our heads around the fact that we are in any way related to Saccorhytus.

For starters, these creatures were only a millimetre in size, with bag-like bodies that wriggled between grains of sand at the bottom of the seabed. They had a giant mouth, which was also most likely used for excreting waste. Other small openings along the body were most likely precursors to gill slits.

However, even if they were not our direct ancestors, the scientists who studied them suggest they could be very similar to something that was.

“In effect what we are suggesting here is that this is the earliest, oldest, most primitive of the deuterostomes,” Simon Conway Morris, professor of palaeobiology at the University of Cambridge, and a co-author of the research, told The Guardian. “This is, if you like, the starting point of an evolution that led ultimately to things as different as a sea urchin, starfish and rabbit.”

Here’s what we do have in common: bilateral symmetry – the left side of the body mirrors the right. It also had skin and muscles, and contracted those muscles to move around, like we do.

These basic evolutionary traits have stood the test of time and can be seen in thousands of species alive today.

Branching out

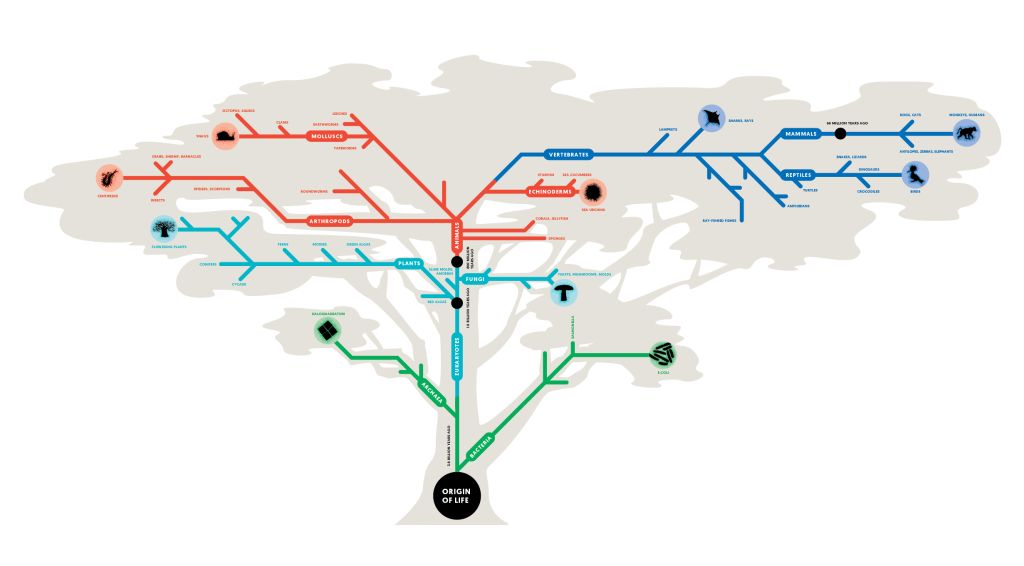

All modern humans, along with our near-human relatives such as Australopithecus or Paranthropus, are merely one small branch on the tree of life.

This is a metaphor used by biologists to help understand the ways in which life has evolved over time.

Like a tree, there are many branches near the top, all jutting out in different directions, and sprouting their own smaller branches. Some reach a dead end and don’t grow any further, much like some animals’ evolutionary mutations that result in extinction.

The further down the tree you go, the fewer branches there are, until you reach one final trunk at the base: the last universal common ancestor (LUCA).

LUCA is the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. It may not have been the first life form – others may have emerged, had a good run, and eventually gone extinct. But LUCA’s genes have been traced in living organisms today, some 3.5-billion years after it is believed to have emerged.

That makes Saccorhytus positively ancient by LUCA’s standards, dated to around 540-million years ago.

Life has come a long way since LUCA and Saccorhytus. We can only imagine what it might look like in another 100-million years, especially in the age of the Homo sapiens.