Shell striations evidence of early tool use by Homo erectus

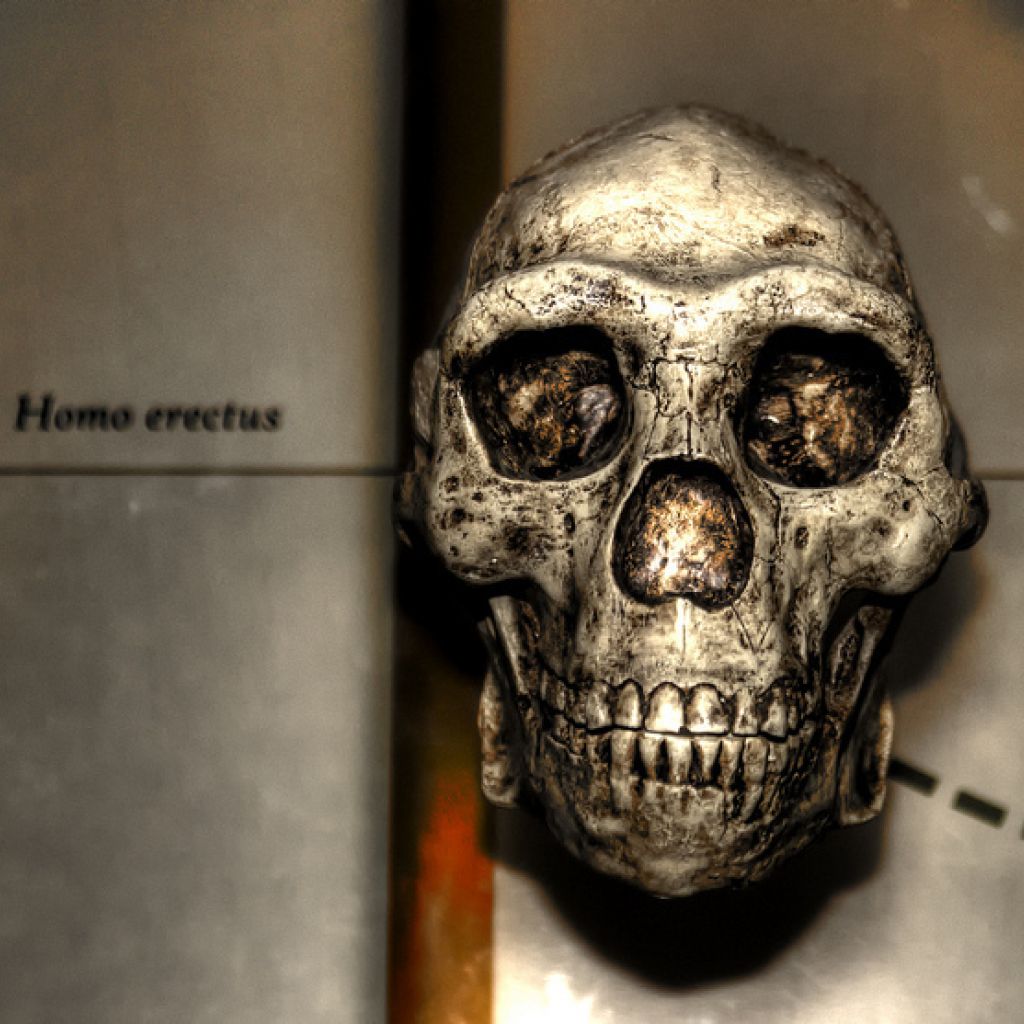

Human bones, estimated to be close to half-a-million years old, were discovered on the banks of the Solo River in Java, Indonesia, during the 1890s by 19th-century physician Eugene Dubois, according to anthropology.net. At the time the remains were referred to as Java Man, later more correctly known as Homo erectus.

The discovery generated great debate in the scientific community when Dubois claimed that Java Man represented a transitional species that fitted into the evolutionary puzzle between apes and humans.

With the subsequent discovery of Homo erectus fossils in Africa and other locations in Asia, his assertions turned out to be correct, giving credence to the possibility of modern-day man being directly related to Homo erectus.

However, recent interest in the discovery has shifted to a variety of shells found alongside the fossils, rather than the fossils themselves. A study of the shells published in Nature suggests that Homo erectus may have found further use for the shells once their contents had been eaten. Research indicates that some of the shells may have been used as tools, while one appears to have been decorated with geometric engravings.

If this turns out to be the case, the shells are representative of the earliest evidence of such decoration and the first-known use of shells as tools.

Of the 166 shells found by Dubois, most belonged to 11 species of now-extinct freshwater mussels of the sub-species Pseudodon vondembuschianus trinilensis.

Initially scientists believed that the molluscs had been transported to the site by water currents, but that was before Josephine Joordens, marine biologist and archaeologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, and Stephen Munro, an archaeologist at Australian National University and a study co-author, took a closer look at the Dubois shell collection.

Close-up photographs of the shells revealed definite markings invisible to the naked eye, prompting Joordens to comment that it’s “strange to see a zigzag pattern on such old fossil shells”.

The researchers compared the Dubois shells to the manner in which living molluscs were buried in the wild to see if there was any conformity in the patterns. They did not find any.

Most shells had holes corresponding to the mussels’ muscle and ligament position.

Half a million years ago on Java, apart from man, other species such as otters, rats and monkeys could also have fed on shellfish, prompting the scientists to figure out which species was responsible.

For their experiments they chose a living mollusc that most closely resembled the ancient Pseudodons, a freshwater mussel called Potamida littoralis.

They tried to pry open the shells with a pointy object that would most likely have been available at the time, a shark tooth. Piercing the muscle caused the shells to open without breaking them. To achieve this result required a dexterity and knowledge, which revealed Homo erectus to be the most likely culprit.

“The opening of shellfish by piercing the valve is unusual, and is not seen in either [early] Homo sapiens or Neanderthal middens,” says Kat Szabo, an archaeologist at the University of Wollongong, Australia.

If humans on Java were opening the shells for consumption, it would appear they ate the shellfish raw. “As bivalves open easily after cooking, this does suggest that the molluscs at Trinil weren’t cooked,” says Szabo.

Another possible reason why Homo erectus might have scraped out the mussel shells was to use the shells as tools. One shell was visibly sharpened, with hallmark striations from contact with hard material. “The shell tool has a knife-like edge, so we assume that it was used for cutting and/or scraping,” says Joordens.

Cut marks found on ancient cow bones in Java may have been caused by shell tools used to butcher animals, cut plants or clean fish. “Neanderthals who lived about 200 000 to 40 000 years ago, also demonstrated the use of shells as tools which they broke and sharpened,” says Enza Spinapolice, an archaeologist at the Max Planck Institute in Germany.

The most intriguing of all the shells in the collection was one with what appears to be zigzagged grooves purposefully carved into the centre of the outer shell. Recreating the pattern on a modern Potamida littoralis shell with a shark tooth provided the closest match to the ancient pattern.